Child healthy weight in Scotland: An ambition running out of time

29 January 2024

In 2018, it appeared that the Scottish Government was boldly recognising this idea and beginning to take stronger action. After years of data showing a high number of young people in Scotland did not have a healthy weight, the Government set out an ambition to halve the proportion of children living with obesity by the year 2030.

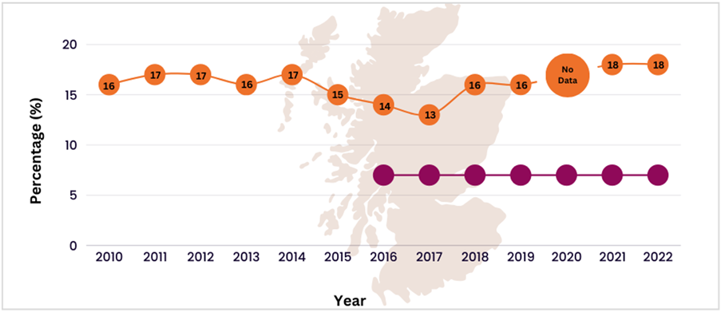

Concerningly, since this announcement, rates of obesity have been heading in the opposite direction. This is confirmed by various data sources in Scotland, including the annual Scottish Health Survey and Primary 1 BMI statistics. The most recent data available in the Scottish Health Survey 2022 shows that 18% of children aged 2-15 are now at risk of developing obesity. To put this into perspective, the prevalence target linked to the 2030 ambition is 7% (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Orange line represents child obesity prevalence reported in Scottish Health Surveys since 2010. Purple line indicates the prevalence target of 7% set from a 2016 baseline.

A subtle direction of travel

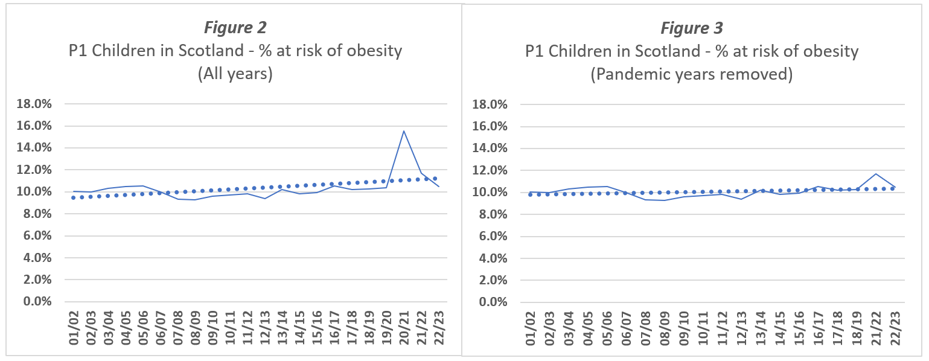

Elsewhere, data from the 2022/23 school year revealed the percentage of Primary 1 children in Scotland at risk of obesity now sits at 10.5%, which is actually a decrease from 11.7% in the year before. However, although it’s always positive to see a reduction in this context, the drop in prevalence is not all that it seems. Statistics from recent years were heavily affected by the pandemic, which resulted in smaller samples sizes along with a spike in higher weights (Figure 2). To demonstrate the overall direction of travel beyond the impact of the pandemic, we carried out a trend analysis of all available years of Primary 1 BMI data and removed the 2019/2020 and 2020/21 cohorts (Figure 3). The slight upward gradient of the trend line in Figure 3 indicates that, despite the drop seen in this year’s data, the overall upward creep in prevalence before the pandemic has continued.

Solid line represents percentage of P1 children at risk of obesity. Dotted line represents linear trend applied to each data set.

Stubborn inequality

Another data pattern of note is the marked inequality that exists between deprivation groups. Primary 1 BMI data for 2021/22 showed that the proportion of children living in the most deprived areas who were at risk of obesity reached 15.5%, compared to 7.3% of children from the least deprived. The latest statistics (2022/23) show these figures are now both lower at 13.9% and 6.8%, respectively. At a glance, this reduction might be viewed as win, but the gap between them has remained virtually unchanged. In other words, even if this reduction continued at a similar rate, the fact would remain that those children from the most deprived areas would still be around twice as likely to be at risk of obesity.

Figure 4 – Number of P1 children in Scotland at risk of obesity from the most and least deprived backgrounds (2022/23). Population coverage of P1 children with valid height and weight measurements in 2022/23 was 89%. One row = approx. 250 children.

Maternal health effects

It is not only during early years that a child might face health challenges related to their weight. A third vital data source for assessing healthy weight in Scotland is the maternal obesity statistics available in the annual Births in Scotland report. Research shows maternal obesity (defined as a BMI greater than 30 at a mother’s antenatal booking appointment) is associated with a number of health complications in offspring, including increased risk of developing unhealthy weight, heart disease, and type 2 diabetes. In 2022/2023, the prevalence of maternal obesity continued to increase and reached a new high of 27.9%. This reflects a slight increase compared to last year’s prevalence of 27.2%. A further 28.6% of maternities are classified as overweight. Another upward trajectory in this particular population group may pose yet more risks to the health of future generations in Scotland.

If not now, then when?

Overall, it is clear that we’re seriously running out of time to meet the 2030 ambition. However, this evidenced lack of progress only adds more urgency to the idea of approaching children’s health differently. In this context, differently means addressing structural drivers that have so far gone unchallenged, instead of placing the burden solely on families. These structural factors include poverty, social cohesion, and, the modern food environment. Encouragingly, there is some evidence that the Scottish Government do remain willing to engage on healthy diet and weight policies needed to make changes. Recent developments include an upcoming consultation on regulating unhealthy food promotions, progress towards implementing an out of home framework focused on healthy eating, as well as a new consultation on Scotland’s National Food Plan as part of the Good Food Nation (Scotland) Act. But these actions have been too slow. We hope that over the next year we will see stronger leadership on ways to improve child healthy weight in Scotland, because if not now, then when?

Weight of the Nation

Weight of the Nation

Healthy Weight Data & Info

Healthy Weight Data & Info

Food & Drink Advertising

Food & Drink Advertising

Price & Promotions

Price & Promotions

Eating out of home

Eating out of home