The Commercial Determinants of Health – explainer blog

12 March 2024

Defining commercial determinants and why they are important

Perhaps unhelpfully, there isn’t yet one set definition for the CDoH. For example, in The Lancet series they describe them as ‘the systems, practices, and pathways through which commercial actors drive health and equity’. Elsewhere the World Health Organization defines them as ‘the private sector activities that affect people’s health, directly or indirectly, positively or negatively’. Thankfully there’s enough overlap in the literature to conclude that the CDoH are generally all about the actions of companies and how they impact society’s health.

So why should we be concerned about how companies operate? After all, the world has often benefited from the actions of private organisations, as implied in the WHO’s definition mentioned above. For example, it is companies that have consistently increased the availability of medicines to dramatically improve life expectancy in recent decades, while issues such as hunger are far rarer now thanks to the power and efficiency of modern food production. It is hard to argue with a status-quo that has produced such positive outcomes thanks to the innovation of industry.

It is hard to argue… until you also see the other side of the same coin. A shocking statistic from the CDoH literature shows that around one third of preventable deaths globally each year are caused by four private industries and their commercial operations (tobacco, unhealthy food, fossil fuel, and alcohol). Other negative impacts created by commercial activities include ongoing damage to the climate and environment, along with growing social and health inequity around the world.

Evidence of excessive damage created by sections of the private sector forms the basis for all work relating to the CDoH and the goal of reducing their prominence. Of course, this mission has largely been implicit in public health efforts for a long time, but the global recognition of the CDoH means it is now being increasingly highlighted and studied more rigorously than ever before.

What are they in practice?

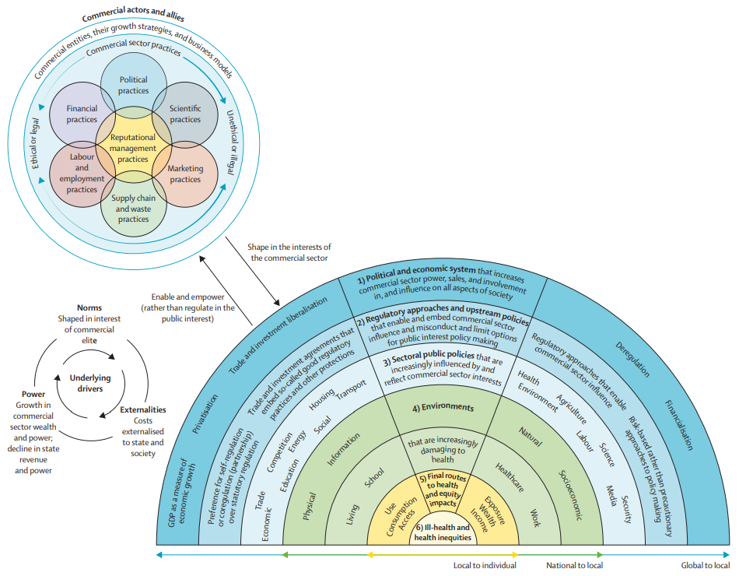

Once we recognise that the CDoH relate to the wide-spread harms caused by certain industries, it’s natural to focus in on the specific products they might sell (e.g., cigarettes, cheap sugary snacks). No doubt, the products and services which eventually damage the health of a person or the environment are a huge part of the problem. However, they do not paint the full picture. As shown in the figure below (specifically in the two most outer layers), the CDoH also relate to the actions which allow harmful industries to maintain their powerful level of influence (and consequently the level of harm they are doing). These high-level actions include things like political lobbying, producing favourable scientific evidence, framing problems inaccurately, and using relentless marketing. It has become clear that harmful industries go to great lengths, often subtly, to protect their own interests at the expense of others.

And this is where the real value of the CDoH concept lies. By using evidence to show that commercial influences are present as far up as government decision making right down to our day to day lives, it allows us to see that this is a system-level issue – something that goes far beyond the power of everyday people. And, therefore, the solutions to address this must also come at the system-level.

Model of the commercial determinants of health. The Lancet. Commercial Determinants of Health 1 - Defining and conceptualising the commercial determinants of health

What can be done?

Experts on the CDoH have proposed recommendations to address the damage being caused by harmful industries. These range from specific actions on harmful products (e.g., regulation of price, availability and marketing) to system-level proposals targeting the political and economic power of the private sector. Examples of interventions at the system-level include enforcing conflict-of-interest guidelines in policymaking, using legislation to protect public health policy from industry interference, and adapting economic indicators to include health as a measure of societal progress. There is a lot of promise in approaching the CDoH from the top-down, because any changes we can see at governance level, both private and public sector, are likely to filter down to the products and services that are put into the world. For the sake of both human and environmental wellbeing, we hope to see more action on the CDoH to help change the rules of the game and rebalance industry priorities.

Food & Drink Advertising

Food & Drink Advertising

Price & Promotions

Price & Promotions

Eating out of home

Eating out of home