Mind the gap - the growing issue of diet-related health inequalities in Scotland

28 April 2022

Health inequalities in Scotland are not new. They have been a significant issue for decades but it is in the last few years in particular that we’ve seen a further worsening of the gradient between the most and least deprived. Progress on life expectancy has been made but this has now been interrupted by austerity, with life expectancy stalling and a widening gap in healthy life expectancy between our most and least deprived communities. The pandemic has made matters worse. A key lesson from the pandemic has been the importance of having a healthy population across the social spectrum, something which Scotland currently lacks.

Health inequalities are a significant problem in Scotland, across a range of measures including diet and healthy weight, and there has been little or no progress made towards tackling them.

We have a growing problem

Recently published data from the National Records for Scotland paints a stark picture of the extent of the problem. In terms of overall life expectancy, males in the most deprived areas have a life expectancy 13.5 years lower than their least deprived counterparts, and for females, the difference between the most and least deprived is 10.2 years.

Scotland continues to face a significant challenge from overweight and obesity, with more than two-thirds of adults having overweight and obesity, and 29% of children at risk of overweight and obesity. This is clearly patterned by deprivation, with those in the most deprived fifth of the population significantly more likely to have overweight and obesity than those in the least deprived quintile.

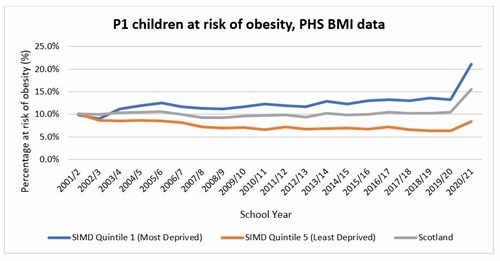

For children, the trend is no different, with clear evidence of persistent and worsening inequalities - 24% of children in the most deprived quintile are at risk of obesity, compared to only 9% in the least deprived quintilei. Data from the primary 1 BMI statistics published in December 2021 further compounds this bleak picture. The biggest increase across weight categories was seen in those at risk of obesity which rose to 15.5% (up from 10% in 2019/20). The 2020/21 school year was the first year to see a large uptick in unhealthy weight, and a widening inequalities gap - 36% of children in the most deprived areas in Scotland are at risk of overweight and obesity, compared to 21% of children from the least deprived areasii. This is the biggest gap seen between the most and least deprived for two decades.

The graph below illustrates the significant inequalities between the most and least deprived in terms of childhood obesity, based on the primary 1 BMI data.

Figure 1: Primary 1 children at risk of obesity, PHS BMI data

We recently wrote a blog where we discussed this data in more detail. It shows a worrying trend for inequalities, and no overall improvement over 20 years.

Impact of the pandemic on health inequalities

Over the past 2 years it has been impossible to ignore the impact of the pandemic of our lives. This impact, however, has not been experienced equally. Many of the restrictions and control measures put in place to limit the impacts of the pandemic have been felt more acutely by those who face the greatest adversity and have as a result worsened health inequalities.

The pandemic has changed our relationship with food and consumption patterns. It has exacerbated existing problems with diets and unhealthy eating and weight, with many people reporting eating more unhealthy foods on a more regular basis. It has also exposed weaknesses and vulnerabilities of our food system. At OAS, we were keen to better understand the impact of the pandemic on food consumption behaviours and so commissioned polling to find out. This polling was carried out in May 2020 and repeated again in March 2021 to monitor the ongoing impact of the pandemic on consumption patterns.

When comparing evidence from the start of the pandemic to a year later in March 2021, there is clear evidence of worsening self-reported health and wellbeing over the course of the pandemic. In March 2021, 60% of polling participants reported that their mental health has got worse since the start of the pandemic, compared to 51% in May 2020, and 40% reported their diet has got worse, compared to 35% in May 2020iii. There has also been a significant increase in the number of people reporting eating takeaways since the start of the pandemic – 31% in March 2021, compared to only 12% in May 2020. A recently published situation report by Food Standards Scotland found that in 2020, compared to 2019 pre-pandemic, the takeaway market in Scotland grew by 31%, to a market value of £1.1bn, with two-thirds of people reporting it is difficult to eat healthily when having a takeaway.

Of course, the picture is not uniform across society, with certain groups more negatively impacted. Our polling activity found that eating out of boredom was the most significant behaviour change reported and that it was more acutely clustered among those with worsening mental wellbeing (67%), young people aged 16-24 (61%), women (59%), people with children (58%), and people working from home (57%), compared to 52% of people overall.

All of these findings paint a worrying picture of worsening diets and widening health inequalities. So, what measures can we take to tackle this?

Tackling inequalities effectively

To tackle health inequalities, action needs to be focused on population level public health interventions which help to address the underlying causes of these inequalities. A continued focus on individual behaviour change interventions will further entrench inequalities. This is because those who are most fortunate have more capacity and resources to respond to such individual interventions, compared to the least fortunate. Focusing on population level public health interventions removes the focus on individualism and incorrect narratives which argue that adverse health outcomes, such as overweight and obesity, are the result of individual choices and fail to acknowledge the profound impact of environments on health outcomes and inequalities. The notion that overweight and obesity is the fault of the individual and a result of poor choices is hugely damaging and needs to be removed from the standard responses of opinion formers and decision-takersiv.

There needs to be prioritisation of population-level public health interventions focused on changing the food environment and addressing structural causes of overweight and obesity, and inequality. This includes action on price, availability and marketing of unhealthy, high in fat, salt and sugar (HFSS) foods.

- Price – make it easier and cheaper to access attractive healthier options. In other words, the healthiest options should also be the easiest and most cost-effective options. Action in this area would include policies which make healthy food the cheapest option and place restrictions on promotions of unhealthy, HFSS foods such as multi-buy promotions, meal deals, and simple price promotions. Evidence shows that HFSS foods make up a significant proportion of in-store promotions and that such promotions can lead to between a 14% and 22% increase in consumption of the promoted productsv.

- Availability - there is a clear link between poorer health outcomes, and areas and population groups with increased availability of unhealthy HFSS foods, and there is a greater clustering of fast food takeaways in more deprived areas. Action in this area would include making changes to the licensing and planning system to control what types of premises are able to open within an area. Currently, planning applications are unable to be controlled on the basis of health; it just does not figure as a material planning consideration. To tackle inequalities effectively and control the availability of HFSS products, health needs to matter to planners to ensure it is at the heart of decision-making processes. We called for this in our submission to the Scottish Government’s recent consultation on draft NPF4.

- Marketing - marketing of products drives purchase and consumption of them. For HFSS foods (and other health harming products), it also drives harm, and this harm is most acutely experienced in more deprived communities. Action in this area would include regulation and control of marketing across all forms of media, including TV, and online. Regulation of TV and online remains a reserved power held by the UK government. The Health and Care Bill, currently going through Westminster, and due to be implemented in October 2022, will introduce a 9pm watershed for HFSS food advertising on TV and a ban on online paid for advertising. We support these measures. The Scottish Government does have some powers to control advertising, largely in the out of home (OOH) sector, and they should take action to tackle the advertising of HFSS foods in the areas where they do have devolved powers.

Our policy asks to tackle health inequalities

The forthcoming Public Health Bill, which the Scottish Government has committed to, presents an opportunity to take action in each of these areas, and make a profound contribution to tackling diet-related health inequalities.

Our key asks for the Public Health Bill are:

- restrictions on all types of in-premises and online retail promotion of HFSS products; including price and non-price promotions, incentivising businesses to increase the amount of healthy food on promotion

- consider mandatory and standardised front of pack nutrition and calorie labelling on all HFSS products, clearly denoting the calories and fat, sugar and salt content per portion if this is not taken forward at UK level or requires legislation to enable a UK wide approach

- action to tackle advertising of HFSS foods in the areas that are within devolved powers, including mandatory national health-protecting outdoor advertising policy that covers outdoor advertising spaces and advertising on transport networks.

Moving forward with each of these actions as part of the Public Health Bill will have a significant positive impact on health and wellbeing for everyone, and help to reduce the currently widening gap in health inequalities.

Out with the Public Health Bill, we are also calling for changes in the out-of-home sector, to shift towards healthier options, including mandatory calorie labelling on menus and controlling portion sizes. The Good Food Nation Bill should be amended, as per the Scottish Food Coalition recommendations, to provide an opportunity and stronger basis for policy coherence across the food system.

The Scottish Parliament Health, Social Care and Sport Committee are currently holding an inquiry into health inequalities in Scotland. Read our response to the call for views for the inquiry here.

References

i Scottish Government (2019) The Scottish Health Survey 2019 Volume 1. Main report https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/statistics/2020/09/scottish-health-survey-2019-volume-1-main-report/documents/scottish-health-survey-2019-edition-volume-1-main-report/scottish-health-survey-2019-edition-volume-1-main-report/govscot%3Adocument/scottish-health-survey-2019-edition-volume-1-main-report.pdf

ii Public Health Scotland (2021) Primary 1 Body Mass Index (BMI) statistics Scotland https://publichealthscotland.scot/publications/primary-1-body-mass-index-bmi-statistics-scotland/primary-1-body-mass-index-bmi-statistics-scotland-school-year-2020-to-2021/

iii Obesity Action Scotland (2022) Impact of Covid-19 control measures on health determinants an overview https://www.obesityactionscotland.org/media/1712/oas-lockdown-polling-further-analysis-2022-final.pdf

iv Government Office for Science (2009) Foresight: Tackling Obesity Future Choices Project Report 2nd edition https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/287937/07-1184x-tackling-obesities-future-choices-report.pdf

v Superlist UK Health 2021. Supermarkets and the promotion of unhealthy food 76335340-81f7-4dc4-b3bf32c49bef0a4f_QM-Superlist-UK_Health_FINAL-perpage.pdf (prismic.io)