Chile's Food Labelling Law

A study published in the Lancet in 2016 revealed that Chileans, on average, consumed 30 kg of processed food products and 170 litres of sugary beverages annually, making them the highest consumers of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) worldwide [2]. Particularly concerning was the excessive consumption of sugar, fat, and salt among children and adolescents, who consistently failed to meet recommended guidelines for physical activity.

Recognising the urgent need to address the rising rates of childhood overweight and obesity, the Chilean Government took decisive action. In January 2016, they enacted the Food Labelling and Advertising Law (FLAL) as part of Law 20 606/2012. This ground breaking legislation encompasses various important aspects, aiming to regulate advertising practices targeted at children and provide labelling guidelines to improve public knowledge about the food and drinks they consume.

The law has two main components:

- Nutritional labelling: All foods and beverages that are high in calories, sugar, sodium, or saturated fat must be labelled with a warning symbol.

- Advertising restrictions: Advertising of products high in calories, sugar, salt, and saturated fat is prohibited in media targeting children under 14 years old or in programmes watched by at least 20% of children. Read our piece on Chile's advertising regulations to find out more.

The food labelling law mandates the implementation of "ALTO EN" warning labels, resembling stop signs, on food items that are deemed high in sugar, sodium, saturated fat, or energy. Furthermore, the law prohibits the sale of labelled products in schools, restricts their advertising during peak hours for children on mass media platforms, and bans the inclusion of toys or figures that may attract minors [4].

Before implementing this law, all Member States of the World Trade Organisation were officially notified, ensuring a public consultation process. Approximately 350 institutions and individuals provided over 3,000 suggestions, observations, and opinions. The feedback included declarations of support for the regulation as well as suggestions for modifications and adjustments to different aspects of the policy.

The main objectives of the labelling regulations:

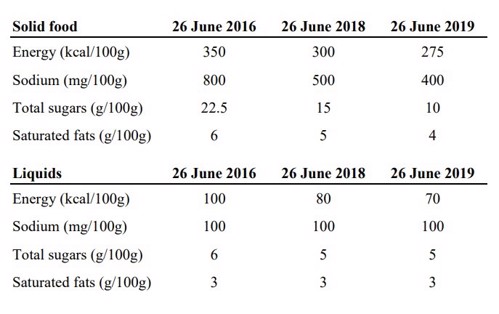

- Food and beverage products containing high levels of calories, sugars, sodium, and saturated fat are required to display a front-of-package label (FoPL). Over time, the limits for these critical nutrients were progressively reduced in three stages. For example, in 2016, a food product would be labelled as having "high sugar content" if it contained more than 22.5 g of sugar per 100 g. However, in the third stage implemented in 2019, this limit was lowered to 10 g per 100g

- Products featuring the FoPL are subject to restrictions on advertising and marketing practices, specifically prohibiting targeting children under the age of 14.

- High-in products are prohibited from being sold in schools, regardless of whether they are packaged or not.

- Schools are required to offer nutritional education and promote physical activity among students [1]

To accommodate the food industry's request for flexibility in implementation, the policy was designed for phased adoption. Each phase involved progressively stricter nutrient thresholds, with the initial phase implemented in June 2016, followed by phase 2 in June 2018, and finally, phase 3 in June 2019 [3].

Implications

The implementation of Chile's food labelling regulations has had significant implications in terms of consumer behaviour and purchasing patterns. It has resulted in substantial reductions in the purchase of high-in foods and beverages, accompanied by a compensatory increase in not-high-in alternatives [3]. Reports indicate that over the course of all three phases, the labelling regulations have led to a 23% decrease in the purchase of high-sugar foods and beverages and a 14% decrease in the purchase of high-sodium foods and beverages [5]. Additionally, the law has been associated with a 10% decrease in the overall calorie content of foods and beverages purchased by Chilean households [3]. 80% of consumers reported that they had noticed the "high in" warning labels after the law was implemented [5].

The law has also led to food manufacturers reformulating their products. A 2021 report by FAO suggests that approximately 15% of the analysed products underwent reformulation following the implementation of the regulation. These products no longer carried the "high in" designation. Reformulation was primarily observed in products categorised as "high in sugar" and "high in sodium." As a result of these changes, the percentage of foods labelled as such decreased by 10%. The categories that saw the most significant reformulations were cold meat (54% reformulated), breakfast cereals (39% reformulated), and milk and dairy products (30% reformulated). Salty spreads, cheese, and drinks also underwent notable reformulations, 25%, 17%, and 15% of the products, respectively.

New Marketing Tactics

In addition to changing the ingredients of some products and eliminating marketing strategies that appeal to children, some food companies also used the reduction or elimination of labels as a marketing tactic [4]. After the law was implemented, certain brands' television ads explicitly stated that they had no labels, had fewer labels, or had fewer labels than the competition. This was a way of advertising themselves as being healthier.

The results showed that 25 brands used this strategy after the implementation of the law. However, 17 of the 25 brands belonged to just four companies: Soprole, CCU, Coca-Cola, and Unilever. These companies were among the most active during the discussion and implementation of the law [4]. The strategy of using labels in television advertising after the implementation of the law coincided with the industry's discourse of cooperation with the new standards.

The FLAL serves as an important example of how public policy can be utilised to improve the food environment in response to concerns over high levels of overweight and obesity. It demonstrates that governments can take action to improve the health of their citizens by regulating the food industry and their marketing techniques, as well as providing consumers with the information they need to make healthy choices.

References

[1] Pfister, F., Pozas, C. (2023) The influence of Chile’s food labeling and advertising law and other factors on dietary and physical activity behavior of elementary students in a peripheral region: a qualitative study. BMC Nutr 9, 11 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40795-023-00671-7

[2] Popkin BM, Hawkes C. Sweetening of the global diet, particularly beverages: patterns, trends, and policy responses. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016;4(2):174–86.

[3] Miquel, J., et al. (2021) Impact of Chile’s food labelling and advertising law on unhealthy food consumption and body mass index in children and adolescents: A longitudinal study. The Lancet Planetary Health, 5(10), e493-e503. doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00172-8

[4] Corvalán, C., Correa, T., Reyes, M. and Paraje, G. (2021) The impact of the Chilean law on food labelling on the food production sector. Santiago, FAO and INTA. https://doi.org/10.4060/cb3298en

[5] Taillie , L., et al. (2021) Changes in food purchases after the Chilean policies on food labelling, marketing, and sales in schools: a before and after study. The Lancet Planetary Health. Elsevier. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanplh/article/PIIS2542-5196(21)00172-8/fulltext

[6] Bachelet VC, Lanas F. Smoking and obesity in Chile’s Third National Health Survey: light and shade. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2018;42:e132. https://doi.org/10.26633/RPSP.2018.132

How Chile regulates food advertising

How Chile regulates food advertising

Chile's Sugar Tax

Chile's Sugar Tax